In the near future, the Dutch police might be able to stop crimes before they even happen. But unlike in the movie Minority Report, they don’t need three mutated psychic humans floating around in a small pool, wooden balls with names carved into them or even Tom Cruise. They have real-time data analytics. And their crystal ball is called the City Pulse project.

In the near future, the Dutch police might be able to stop crimes before they even happen. But unlike in the movie Minority Report, they don’t need three mutated psychic humans floating around in a small pool, wooden balls with names carved into them or even Tom Cruise. They have real-time data analytics. And their crystal ball is called the City Pulse project.

In collaboration with several tech partners, the Dutch police is now able to detect possibly escalating situations so officers can intervene prematurely.

A network of sound sensors measures the (rising) levels of aggression on the ground and alerts police through a smartphone notification, in real-time, to let them know where the incident is taking place.

The City Pulse project is being tested in Stratumseind: a popular street and nightlife center in the Dutch city Eindhoven. In the span of just 250 meters, Stratumseind is home to 55 bars and 10 dinners, with 20.000 (young) visitors during the weekend.

Unfortunately, this also makes the street a hotbed for violence. On a yearly basis, 800 incidents take place in Stratumseind — 90% of all nightlife related incidents in Eindhoven — over two incidents per night.

Nudging people with smell and sound

So together with the city of Eindhoven and tech companies such as Atos, Sorama and Axis, the Dutch police started an experiment to increase safety in Stratumseind. The street turned into a living lab where lights, cameras, recorders, real-time analytics (and soon smell) are used to test if they could change the mood of visitors and prevent violence.

To talk about these predictive technologies — and their impact on privacy — I visited the police station in Eindhoven to meet Leon Verver, the director of the Dutch Institute for Technology, Safety & Security (DITSS).

The DITSS originated as a collaboration between high tech growth accelerator Brainport, the city of Eindhoven and the Dutch police. Although the organization is staffed by tech-savvy police officials, it can operate independently from the police force. “Because there are fewer organizational layers, we can rapidly take action and achieve quicker results,” explains Verver, who is a police officer himself but spends most of his time as the director of DITSS.

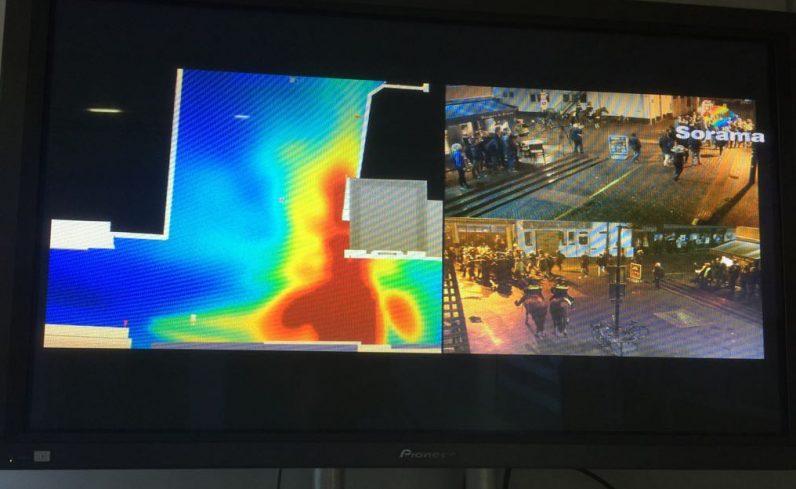

Together, we are looking at security footage of Stratumseind. Next to the security footage, the screen shows an ‘aggression heat map’ and a map of Stratumseind.

Reducing response time drastically

Verver sets the scene. “It is four o’clock at night. A group of people approaches.” On screen we see one guy grab another guy. The ‘sound heat map’ starts to glow. It signals ‘sound detected’ and a location pointer appears on the map of the street. Moments later, a fight breaks out.

Every moment now I expect the police to show up and break up the fight. But the officers in the video don’t have access to the new technology. In other words: nothing is happening. “The police officers could have been there almost immediately because they’re standing just around the corner,” explains Verver. “But they don’t hear or see the fight.”

Not until some passerby alerts the police, do they rush from around the corner, break up the fight and block off the street. The whole event takes a minute and a half. “With this technology, we can get this response time down to five seconds,” Verver tells me.

The potential for predictive analytics is huge and its scope is not just limited to nightlife. Other Dutch cities are now working on similar predictive projects.

“We are experimenting with data to be able to anticipate how neighborhoods will develop — so that we can detect and put-down early signs of criminal activity,” Verver explains.

“Another project is the zero-burglary-neighborhood,” he continues. “By having citizens share data and placing sensors in neighborhoods, we aim to disrupt an incident before it has taken place. For example, detecting the sound of a burglary tool or method. Also, if we see individuals acting suspicious, we can send someone by to prevent anything from happening.”

Calibrated differently, this sound recognition technology can also be used to locate underground weed farms (lamps and vents make sounds, some inaudible to the human ear) and illegal immigrants coming into Dutch harbors. “The technology shows big promise when it comes to detection of criminal activity,” says Verver.

Sensitive topic

According to Verver, technology is becoming inseparable from police work. It will enhance policing and allow officers to respond to threats faster.

But it’s also a sensitive topic. “Many people believe that the policemen and women belong in the field, making sure our streets are safe,” Verver tells me. “But I want an efficient police force that makes the right choices — not one that is just driving in circles on the block. By creating this network, we can limit the distance to potential crimes and stay on top of everything that goes on.

Not everybody is a fan, however. Critics and privacy experts point out that people have a right to privacy in public spaces. The people of Stratumseind never agreed with being monitored and giving up their privacy. Yet here are twenty sensors paid for by the government, the police and big businesses who are collecting data around the clock. The idea of Stratumseind might be noble, but technology is evolving too rapid in the public space with the law only coming in second, critics argue.

“I know there are a lot of people who are very against what we do — and they bring up valid points. I wouldn’t want to be monitored myself all the time. But we make a big distinction between which data we do need for our operations and which we don’t,” Verver explains.

Verver ensures me that they don’t use or save any personalized data. “We are not listening in on people or record what they’re saying. We filter the total data spectrum for the information we need — that’s all.”

In case of the City Pulse project, the sensors measure emotions in voices and sound levels. Officers in the field will only receive a marker on a map where the incident takes place.

“We should always maintain a proper balance between the use and range of our tools and the impact on the privacy of innocent bystanders,” argues Verver. Whether or not to use certain tools depends on the suspected level of violence.

After years of testing, the predictive City Pulse project is now moving into its operational phase. This means police officers in Eindhoven will soon be equipped with the tools to locate aggression and predict fights from breaking out. But Verver envisions this technology everywhere in the Netherlands, even the world.

“Hopefully, what we do here will lead to a significant drop in violent incidents. That’s what it’s all about, after all — reducing violence — and that’s why I believe his technology should be used everywhere.”